A review of school textbooks in Pakistan has found that problematic content remains embedded in the curriculum, contributing to the exclusion of religious minorities from the country’s social mainstream and national narrative.

A study titled What Are We Teaching at School? by the Lahore-based research and advocacy organization Center for Social Justice (CSJ) reviewed 145 textbooks of compulsory subjects for Grades 1 through 10. The subjects included English, Urdu, General Knowledge, Social Studies, History and Pakistan Studies in use by both public and private schools during the 2022–2023 academic year.

The study found that religious content was heavily embedded in non-religious subjects, effectively making it compulsory for all students—including non-Muslims—to study and pass exams on Islamic teachings.

“The excessive material from the majority religion in compulsory subjects disproportionately affects students from religious minorities, forcing them to study content that may not align with their faith or personal beliefs,” the report noted.

The highest percentage of religious content was found in textbooks from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province (39.6%) and Punjab province (39.4%), followed by the National Book Foundation (29.8%), Balochistan province (25.9%) and Sindh province (18.7%).

Subjects with the highest concentration of religious content were Pakistan Studies (58%), followed by Urdu (38%), Social Studies (33.1%), History (26.8%), English (24.2%) and General Knowledge (12.3%).

The report noted that textbooks lacked alternative content for minority students, making Islamic teachings in non-religious subjects unavoidable. Examples included chapters on the caliphs, Seerat (life of Prophet Muhammad), Naat (poetry in praise of Prophet Muhammad) and Hamd (poetry in praise of God) appearing in Urdu and English language subjects, despite being religious topics.

The study also highlighted that Islamic terminology in English textbooks—such as using “Allah” instead of “God” and “Masjid” instead of “Mosque”—reinforced linguistic dominance. Arabic honorifics for Prophet Muhammad appeared frequently in various subjects, making it difficult for minority students to read, memorize or write.

“Moreover, when students progress to higher grades, the volume of religious content increases, particularly in subjects where it does not naturally belong. For instance, Grade 9 English textbooks contain chapters like ‘Hazrat Muhammad – The Model of Tolerance’ and ‘The Madina Charter.’ Grade 10 Urdu textbooks feature ‘Simplicity and Humility of Hazrat Muhammad’ and ‘Hazrat Umar,’ which should belong in Islamic Studies rather than compulsory language courses,” it noted.

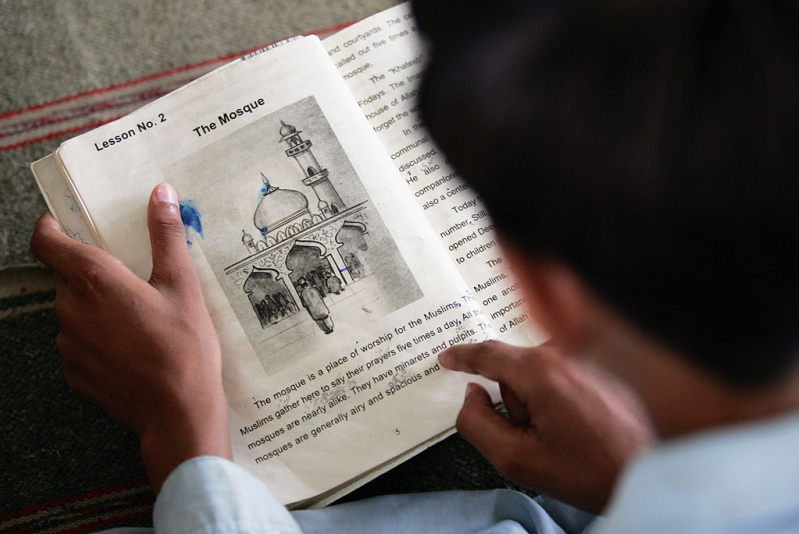

The study found that religious imagery—particularly of places of worship—was also imbalanced. “At least 389 images were used across compulsory subjects like Urdu, English, and social sciences. Minority places of worship found little space from Grades 1 to 10. Christian churches and Hindu temples were each pictured seven times, Sikh gurdwaras four times, while those of Baha’i, Kalasha, Buddhist and Zoroastrian communities were absent,” the report noted.

Mosques remained highly represented in textbooks published by textbook boards in three of the four provinces and by the National Book Foundation.

“Each of them featured between 56 and 61 images of mosques. Only the textbook board in Sindh province showed comparatively fewer images of mosques at 23.

“The overwhelming representation of majority religious sites and the underrepresentation of worship places of minorities underscores an imbalance in the education system,” the report stated.

The study emphasized that embedding Islamic content and mosque imagery in non-religious subjects violated Article 22 of Pakistan’s Constitution, which prohibits compulsory religious instruction for students of other faiths.

“This places minority students at a relative disadvantage compared to their Muslim classmates, who also study the same content in Islamic Studies, already a compulsory subject for them,” it stated.

The review also found examples of hate content and derogatory language in textbooks. These included references to “Hindus’ mentality,” the “complete dominance of Hindus over Muslims,” and references to the caste system, such as “untouchables” and “low caste.”

Subjects where such content was most prevalent included Pakistan Studies (15%), followed by History (4%) and Urdu (0.66%). Social Studies, History and Pakistan Studies textbooks frequently presented religious groups in a one-sided way, portraying one as a victim and another as an oppressor, limiting students’ understanding of complex historical realities, the study found.

In 2023, the National Curriculum Council approved the publication of religion textbooks for seven minority faiths—Hinduism, Sikhism, Christianity, Baha’i, Zoroastrianism, Kalasha and Buddhism.

However, CSJ noted that implementation of this policy—including the availability of qualified teachers—was slow, especially in schools where only one or two students belonged to minority faiths.

The study found that the ratio of inclusive content in textbooks varied across provinces, with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (7%) and the National Book Foundation (7%) leading, followed by Sindh (6.4%), Balochistan (5.4%) and Punjab (5.2%). Despite a slightly lower percentage of inclusive chapters, the Sindh Textbook Board showed a more comprehensive approach by including diverse protagonists and references to multiple religious festivals, reflecting an effort toward representation and acceptance.

By contrast, Punjab and Balochistan had the least inclusive content, offering only occasional mentions of women’s contributions or persons with disabilities, with little depth or consistency.

“Subjects such as Social Studies (13%) and History (14.2%) contained the highest proportion of inclusive content, while Urdu (3.2%), General Knowledge (5.4%) and English (6.5%) remained less inclusive. Some notable examples of inclusivity include the mention of diverse names like Vicky, Rita, Priya and John; religious festivals such as Christmas, Holi and Eid; and women role models, including Dr. Ruth Pfau,” the report noted.

The CSJ urged the government to develop school and college curricula that promote religious and social tolerance.

It also called on authorities to refrain from introducing legislation or policies that violate constitutional protections of religious freedom and non-discrimination, as outlined in Articles 20, 22(1) and 25 of Pakistan’s Constitution.

“The government should ensure that textbooks of compulsory subjects for students of all faiths do not include content that could be construed as preaching any faith, ensuring full compliance with Article 22 (1) of the Constitution of Pakistan, which guarantees that no student shall be compelled to receive religious instruction other than their beliefs.

“Additionally, it should ensure that textbooks for compulsory subjects should not contain any lesson that projects the superiority of one faith over others, thereby fostering an inclusive and unbiased learning environment for all students.”

The report also called for equitable representation of all religious communities by incorporating content on their beliefs, practices, places of worship and festivals to reflect Pakistan’s diversity and strengthen social cohesion.

It added that incorporating positive narratives that emphasize shared heritage, cultural diversity and the contributions of minority communities to Pakistan’s history and development would foster a sense of belonging and mutual respect among students from all backgrounds.

Finally, the CSJ urged the government to conduct independent reviews of curricula and textbooks before publication to identify and remove bias, close content gaps and ensure that educational materials are inclusive and equitable.

Hindus remain Pakistan’s largest religious minority, comprising 1.61% of the country’s population of 240 million. According to 2023 data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Christians account for 1.37%, while Muslims make up 96.35%. Other minorities, including Sikhs, Buddhists and Zoroastrians, make up less than 1%.