Two previously unknown letters by British politician and Christian abolitionist William Wilberforce have been unearthed in the archives of the University of Chester, shedding light on the later years of his life and ministry.

In a June 18 press release, the university confirmed that the 19th-century letters—written in 1830 and addressed to Rev. Henry Raikes—were found by staff while cataloguing materials for a new alumni archive.

The letters were penned by Wilberforce to Rev. Henry Raikes, son of his close friend Thomas Raikes, who was Governor of the Bank of England between 1797 and 1799. Henry Raikes was appointed Chancellor of the Diocese of Chester by his friend Bishop John Bird Sumner and was one of six founders of the Chester Diocesan Training College, which later became the University of Chester.

The Wilberforce letters, dated 1830, detail efforts by him to build a chapel near his home in Highwood Hill, Middlesex.

Dr Hannah Ewence, Head of Humanities, Cultures and Environment at the university, explained the motivations of Wilberforce at the time he wrote the two letters.

“These two letters, between William Wilberforce and his friend and fellow Evangelist Henry Raikes, were written towards the end of Wilberforce’s life,” said Ewence.

“The campaign which had dominated Wilberforce’s political career—the abolition of the slave trade—had achieved the momentous milestone of prohibiting the buying and selling of slaves within the British Empire, in 1807. The abolition of the trade itself would not be realised until 1833; the year of Wilberforce’s death.

"By 1830, failing health had caused Wilberforce to retire from politics and from London life, moving from Grove House in Brompton to the relative tranquillity of Mill Hill, Middlesex (now in the north London borough of Barnet).”

It was from Highwood House that Wilberforce sat down to pen his replies to Raikes, then Chancellor of the Diocese of Chester, added Ewence.

“Their affectionate correspondence ranged across personal, political and spiritual matters, and offers a sense of the paternal regard in which Wilberforce held the younger man,” she said.

“Certainly, his efforts to persuade Raikes that he should take a living as curate in Mill Hill because he knew him to be ‘a promoter of peace and good will’ reveals that Wilberforce’s reputation for showing great care for friend and stranger alike had not diminished, even in his final years.”

Ewence believed it “somewhat tragic” that Wilberforce’s ambitions to build a chapel near his home in Middlesex, the main discussion point of the letters, were not realised during his time living there.

“By the end of the year, the catastrophic failure of his eldest son’s commercial venture into the dairy business presented Wilberforce with few options except to let Highwood House,” she added.

“Thereafter, Wilberforce became somewhat nomadic, living out his final years between his children’s homes in Kent and the Isle of Wight, and the hospitality of friends.”

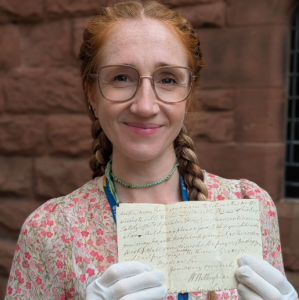

The two letters were discovered as part of a project to organise and develop the university archive led by Alumni Assistant, Amy Hultum, with support from Dr Lisa Peters. The project is unveiling donations from alumni and other artefacts held in storage at the university for a long time.

“We did not expect to come across anything like these letters but we were very excited to find them in a box amongst our University collections,” said Hultum, about the discovery of the letters.

The two letters by Wilberforce were found alongside two other letters. These other messages dated from 1808 and 1809; with one letter to Henry Raikes from his uncle and the other letter to Thomas Raikes from his brother.

Wilberforce died in July 1833 and was buried in Westminster Abbey. The chapel that he dreamt of building at Mill Hill was consecrated that same year.