I have followed comments by critics of the World Watch List (WWL) in the global media for many years. The yearly WWL is the most quoted tool regarding freedom of religion or belief (FoRB, the official term used by the United Nations), even though it only researches the situation of Christians.

While I am sympathetic toward serious efforts to record restrictions on religious freedom worldwide and advocate on behalf of churches, my opinion in this article is as a professor of the sociology of religions. My opinion does not represent WWL or any of its partners. I would, however, like to see the watch list expanded to include a global study and ranking of all religions and worldviews under threat.

Criticisms of the WWL in the media fall into six major categories, and each is addressed here:

1. The definition of persecution is too broad.

There is no definitive agreement about what persecution is.

We have to distinguish between two questions here. Firstly, there is no definitive agreement about what persecution is. To argue that WWL's definition is too broad misunderstands that WWL has established its own definitions and their published results line up with that. Disagreeing with the definition and questioning the validity of the results WWL publishes are two different issues.

How should we define or describe persecution in relation to religious convictions, independent of Christianity? I asked an AI assistant to summarize all available definitions, and received the following response: "Religious persecution is the systematic mistreatment and oppression of individuals or groups due to their religious beliefs or practices. It involves oppression, discrimination, violence, or harassment aimed at suppressing religious affiliation or the lack thereof. Common forms include arrests, property destruction, forced assimilation, or denial of rights."

I agree. While there is no singular definition, many researchers describe religious persecution similarly, as does the Wikipedia. For example, in his book Religious Persecution and Political Order in the United States, David T. Smith defines it as "violence or discrimination against members of a religious minority because of their religious affiliation"

"Persecution" is also used as a legal term in various treaties and laws, most importantly in the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, and in asylum laws in the US, the EU and many other countries. While definitions vary, they all agree that violations of human rights must be severe and real before the term can be applied to asylum cases or appeals for refugee status. With the term "discrimination" shaping global thinking in increasing measure, how we understand persecution increasingly incorporates discrimination as well, in alignment with how WWL views persecution.

Nevertheless, things can be tricky. For example, imagine that your children are forbidden from studying at university or that you cannot become a police officer in your country because of your religious affiliation. Could this form of discrimination by itself indicate persecution? What about if you do not apply for a place at university or for a police job because you are aware of the situation? Or does it only become persecution when you actually apply and then encounter all kinds of problems? Take ten such cases to ten German courts and you will get ten different answers.

Most human rights terms and related words have broader general and narrower legal usages.

Please be aware that most human rights terms and related words have broader general and narrower legal usages. For example, the terms "sexual abuse", "sexual violence", and "rape" are often used very generally in the media, but that usage is not necessarily in line with what the law and courts of a given nation might determine.

2. By claiming that "Islamic oppression" is one of the "persecution engines", WWL reveals its Christian bias.

Here are the so-called "persecution engines" that WWL identified in their data when they considered the most common motives behind persecution:

- Islamic oppression

- Religious nationalism

- Clan oppression

- Ethno-religious enmity

- Christian denominational protectionism

- Communist and post-Communist oppression

- Dictatorial paranoia

- Organized corruption

- Organized crime

This includes "Christian denominational protectionism". Is this anti-Christian bias? What about "religious nationalism"? This includes countries whose nationalism is built around a form of Christianity, such as Russia.

"Islamic oppression" does not mean that all Muslims are oppressive.

"Islamic oppression" does not mean that all Muslims are oppressive, just as "Christian denominational protectionism" does not mean that this is typical of most church groups. One thing is certain: one cannot leave out oppression from Islamic sources when talking about the global violation of human rights to freedom of religion or belief.

It is fair to say that these persecution engines are proven by the WWL only in relation to Christians. However, if we look at the data that the International Institute for Religious Freedom is gathering on all religions and look at other reports like the bi-annual one from PEW Research Center or the yearly report from or Catholic friends Aid to the Church in Need, no major persecution engine is missing when studying the persecution of Muslims (as a multifaceted world religion), or the Bahá'í Faith or Jehovah's Witnesses (as two representatives of smaller religions).

This is not to say that naming the eight persecution engines is the best approach or the final word. But that criticism of WWL being biased, speaking only against one religion, is unfair. Including Islamic oppression is necessary, but it's not the only motive identified by WWL.

3. Is Christianity really the most persecuted religion in the world? Or is the number simply high because Christianity is the largest religion in the world?

Many Westerners are unaware of the persecution of Christians at all.

In answer to the third criticism of WWL, the WWL team say: "Christians are by far the largest religious group persecuted in absolute numbers". Given that many Westerners are unaware of the persecution of Christians at all and assume that the situation of Christians elsewhere in the world is similar to that on their own continent, this is an important statement to raise awareness. Remember that stating that women are the majority of victims of domestic violence does not downplay or excuse female violence against men. The same is true here.

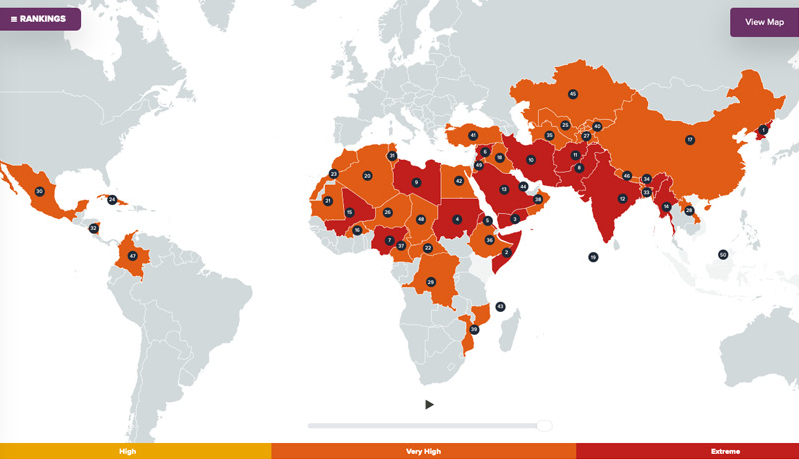

The Pew Research Center produces a global report on Restrictions on Religions every two years; the most recent one was in 2024, the next is expected this year. In its 12th report in 2021, it stated that Christianity is the most persecuted religion, followed by Islam. They did not consider absolute numbers, but rather the number of countries with restrictions: 153 for Christianity and 147 for Islam. As with the WWL, one might have an opinion on how valid these assessments are. Nevertheless, such statements can be accurate so long as everyone clearly defines their terms.

Neither the WWL statement nor the Pew statement mentions that Christianity is the religion with the highest percentage of affiliates being persecuted. In order to make this statement, one would first need to study all religions in detail. The 380 million WWL Christians would account for around 15% of Christians worldwide. That is a large number of individuals. But put in per capita terms, there may be religious groups with a similar or slightly higher percentage over their entire adherents.

In sum, I would certainly advise WWL to issue a longer statement on this matter. They could mention that it is easier to ask for percentages when focusing on a specific question. For example, in which countries can Christians and affiliates of other religions not be employed by the state, e.g. as police officers, or where are they not allowed to build official places of worship?

4. Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and others criticize the fact that this research focuses only on Christians. They argue that this is merely a tactic to pit religions against each other.

This criticism deserves most attention. Firstly, critics like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have never shown evidence that freedom of religion or belief is a high priority for them. Furthermore, they have always played down the persecution of Christians e.g. in Nigeria.

On the other hand, critics from the global community of freedom of religion or belief advocates and researchers, who definitely want to include persecuted Christians in the overall picture, would also like to see WWL expand its approach to include all religions and faiths.

In both cases, such criticism should be carefully studied, even if WWL's focus remains on researching the situation of Christians only (as is their right). Even if it were wrong to research only the situation of Christians, this would not automatically call into question the validity of the data that WWL provides. The solution would not be to stop publishing WWL, but to use their data as part of a larger project that covers all other religions (by a group with greater capacity).

There is no basis for the criticism they receive in this regard.

That said, in its country reports (but not in the statistics), WWL mentions the persecution of other religions and speaks up for the freedom of all. In addition, they never make all Muslims or all clans etc. responsible for the persecution, nor do they use racist language against any group. WWL could be improved, but there is no basis for the criticism they receive in this regard.

It is common for religious and worldview groups to fight for themselves and their own people. If one wants to criticize this, one should criticize all, not just WWL. At the United Nations, the Baháʼí, Jews, Humanists, and others have offices defending their people, from which they publish reports on the situation of their followers. Many religious groups publish reports on their own situation worldwide or in specific regions or countries. After all, it is much easier to gather information about your own group than about others. I rarely hear criticism of other groups; it is usually only Christians who are criticized.

Researchers studying all religions are usually independent researchers or political bodies. They tend to be outsiders to the group, rather than participants of the religions or as part of organizations identifying with each religion. For example, the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), which represents 57 states including some from the Americas, and is world-class in its work against hate speech and discrimination, organizes large databases for people to report incidents of hate speech and discrimination. The ODIHR gathers those data as an independent body, and their data is used specifically and separately by Jews, Muslims, Christians, and followers of other religions.

Open Doors, the creator of the WWL, receives its funds from Christian donors who want to support churches facing discrimination and persecution. But in contrast to external research groups, Open Doors is deeply involved in the group they are advocating for.

Only a very small percentage of donations is used for research.

For example, they provide support for families whose sole breadwinner has been imprisoned. They help rebuild churches that were destroyed. Only a very small percentage of donations is used for research, because they must be careful to fulfill the donors' wishes to support those being persecuted. This resource limitation constrains the scope of research for WWL.

From my experience on the boards of many NGOs I contend that it would be unrealistic to ask Open Doors to pay for yearly research into all religions. It would cost many times more and would have to involve a complex set of institutional partners.

In another example of criticism about WWL's limited scope, the Catholic Church and the larger Protestant churches in Germany published a report against WWL for focusing solely on Christians. As they say, "talk is cheap". While they advise on what religious freedom research should do, they did not offer to finance broader research. The former German state churches, now independent, both Catholic and Protestant, have a combined annual budget of around 12 billion Euros (at least, not counting the budgets of local churches). It would be very easy for them to fund the best possible religious freedom research. Meanwhile, the Vatican News obviously thinks otherwise and uses the WWL's numbers, summarizing the results each year.

We conduct an annual audit of each WWL before it is published.

At the International Institute for Religious Freedom, we conduct an annual audit of each WWL before it is published. Similar to a financial audit, we have the right to see anything we want, and we choose the sample countries and then follow through, looking at the sources and how they are documented, and so on. We assess whether or not all protocols have been followed correctly, as well as with criticism and proposals for improvements. You can click on this link to find our 2026 audit statement. The WWL researchers take seriously our proposals for improvements.

I believe it would not be too difficult to create a WWL for all religions. All that is needed is funding. I have approached critics on more than one occasion to say, "Give us the funds and the IIRF will produce a similar report for all religions." So far, to little effect.

The WWL and the IIRF are the only organizations that I know of that actually document killings because of religious affiliation: the WWL for Christians and the IIRF's Violent Incidents Database (VID) for all religions. The VID could be much more complete and useful if those criticizing the lack of numbers for non-Christians helped to finance this kind of research. Yet most of the funds for the VID still come from Christian organizations.

5. One should not create a ranking at all.

Much of our knowledge about the world today comes from such rankings.

WWL is just one of many such rankings worldwide. Billions of dollars are spent on these kinds of rankings. Organizations like the World Bank produce them because otherwise they would have no idea what is going on. Much of our knowledge about the world today comes from such rankings.

Other groups, even like consumer protection organizations, are familiar with such research procedures. What is the best car for a family of four? You single out five areas in which you can get a certain number of points: price, duration, interior space, fuel usage, etc. In the end, you have a ranking. But now you are only interested in how much petrol or electricity a car needs. You turn to the relevant column and easily see the ranking for fuel usage.

Several global corruption indices from Transparency International, the Freedom Index from Freedom House and many UN indices on poverty or equal rights for women follow the same basic methodology that WWL follows. If you are only interested in the killings of Christians and actual violence, check column 5 of the WWL. A country might have a high ranking here, but a lower one in the other four columns. Conversely, a country may have a high ranking in columns 1–4, even though few people are killed.

6. Is WWL really academic research?

There are inherent limitations on this type of research in our imperfect world.

I have seen WWL evolve from a resource for praying for and supporting Christians in hostile contexts to the report most frequently referenced by the global secular media year on year. The IIRF collaborated with WWL academics from various disciplines to develop the five-column questionnaire, which is refined annually to enhance reporting. Yes, there are inherent limitations on this type of research in our imperfect world. We need to accept that perfect numbers will always be elusive.

IIRF works with the research team academics at WWL to ensure that the results are presented in a way that makes it clear how they are achieved, enabling researchers to study the methodology. Our latest audit report shows that we are not doing WWL any favors or simply giving them a clean bill of health. Instead, we are digging deep into what they do and providing a scientific evaluation, which may differ from year to year, as a financial audit would.

As is often the case, the published methodology of WWL has many more pages than all the other material published around the WWL. It provides definitions for all the terms used and explains how the final score for each country is calculated. Similar to the Pew Research Center's Freedom of Religion or Belief methodology report, researchers can find much more information in WWL's report than for many other well-known global annual rankings, such as Transparency International's various corruption scores. If you take time to read WWL's methodology, you will easily understand why this kind of research is so expensive!

Finally, like WWL, an advantage of the IIRF's Violent Incidents Database (VID) is that the raw data is available to anyone (although, now via a necessary subscription model to help with costs). This means that researchers can access the data for their own research as well as ask and answer questions that are not currently on IIRF's agenda. If we had the necessary funding, IIRF could expand the Violent Incidents Database and its other tools, producing many reports related to freedom of religion or belief and reporting on human rights violations against any given faith group.

Archbishop and Professor Thomas Paul Schirrmacher is the President of both the International Council of the International Society for Human Rights in Frankfurt and the International Institute for Religious Freedom in Costa Rica and Bonn. He was Secretary General of the World Evangelical Alliance from 2021 to 2024. Prior to this, he served the WEA for 25 years in various roles, including Associate Secretary General for Theological Concerns and Intrafaith and Interfaith Relations. He travels to over 50 countries a year, meeting heads of state and government, religious leaders, and heads of churches of all confessions on behalf of the persecuted church, as well as fighting human trafficking and corruption.

The International Institute for Religious Freedom (IIRF) was founded in 2005 with the mission to promote religious freedom for all faiths from an academic perspective. The IIRF aspires to be an authoritative voice on religious freedom. They provide reliable and unbiased data on religious freedom—beyond anecdotal evidence—to strengthen academic research on the topic and to inform public policy at all levels. The IIRF's research results are disseminated through the International Journal for Religious Freedom and other publications. A particular emphasis of the IIRF is to encourage the study of religious freedom in tertiary institutions through its inclusion in educational curricula and by supporting postgraduate students with research projects.