In the heart of Hanover Park, a neighborhood etched into the Cape Flats of South Africa's vibrant, yet deeply unequal, city of Cape Town, Pastor Craven Engel and his dedicated team from a local church stand as a beacon of resistance against an unrelenting tide of violence.

This community, described as a "depressing neighbourhood of drab buildings and unemployed young men" by a BBC Africa documentary that recently trailed the dangerous but critical work that Pastor Engel and his team does, is but one "island in a violent gangland archipelago" where gunshots and stabbings echo almost daily.

Cape Town, paradoxically one of Africa's wealthiest cities and equally one of the most unequal, grapples with its stark reality as the country's gang capital, plagued by a murder rate of 70 per 100,000 – double the national average. This grim statistic, underscored by the fact that 263 gang murders were reported in the Western Cape in just three months in 2024, including 79 child deaths from gunshot wounds or stabbings, paints a chilling picture.

Gangs actively recruit children as young as eight to fifteen years old, according to the BBC, leading to horrific scenarios where an entire group of children can be gunned down if a single child gangster is among them. Such pervasive violence means emergency services and police often avoid these dangerous zones, leaving residents feeling abandoned.

Ex-gangsters building bridges

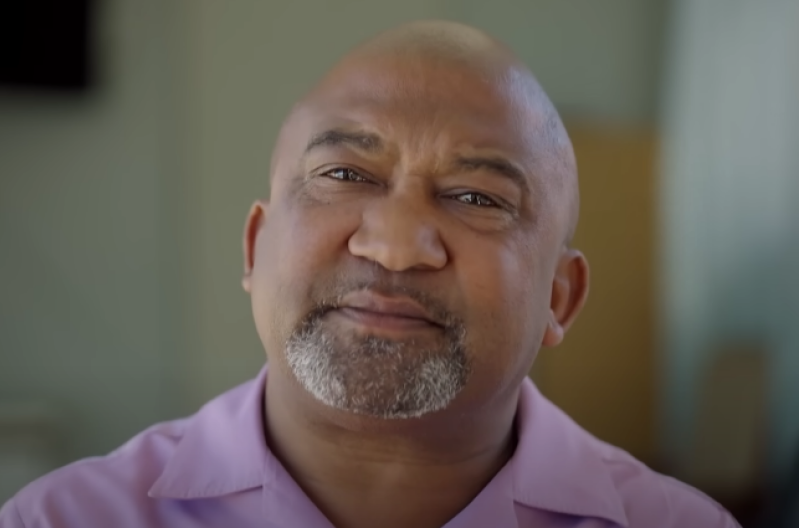

It is against this harrowing backdrop that Pastor Engel founded Ceasefire, an NGO that since 2013 has adopted a model of community-based "violence interrupters." Pastor Engel is driven by a mission to "reduce the violence within the community so that people can be safer, kids can walk safely to school and children can play outside."

Pastor Engel and his team – notably composed of reformed gangsters – treat violence like a disease, focusing on its "detection, interruption, and changing mindsets." His team, which operates from the First Community Resource Centre in Hanover Park, is uniquely equipped, largely comprising reformed gangsters, chosen for their "skill-sets and experience." As Engel explains, these interrupters "have to be credible in the community; they must have changed their lives," and critically, "they must understand prison culture, gang culture, and the gangs must respect them."

They are on the front lines, aiming to bring a measure of peace to an environment shaped by apartheid-era forced removals where social control over the youth was lost and the drug trade became the "most thriving economy."

“Almost 70% of our young people are addicted to some kind of substance - heroin or cocaine,” Pastor Engel said. “Most of them are environmentally contaminated with violence, with drugs, and with domestic violence, and this trauma is not dealt with so they end up using different kinds of substance just to tone down the trauma in their brains.”

Ceasefire mediators actively intervene in gang conflicts, striving to get gangs to talk to one another and negotiating temporary ceasefires between warring factions. Supported by charitable donations, the program includes a rehabilitation plan designed to help ex-gang members overcome drug addiction and find employment. Pastor Engel stated that the Ceasefire program has rehabilitated 168 "high-risk" gangsters.

One of the reformed gang members is Wesley, who was driven by revenge to join the Ghetto Kids at age 12. He spent 18 years as a gangster, rising to become the "right-hand man" of his gang leader, during which time approximately 30 of his friends were killed. Today, he has turned his life around and is admired by the community. "The community knows your story and knows your past and respects you only when you have turned around," Wesley affirms, "they do not judge you anymore."

Challenges and unyielding hope

Despite these profound individual successes, Ceasefire faces significant hurdles. The program has been crippled by funding cuts from the city, forcing its dedicated conflict negotiators to work on a voluntary basis, balancing their street work with the need to support their families. The pervasive violence remains an enduring challenge, with peace rarely lasting more than a few days in Hanover Park. Even during delicate ceasefire negotiations, tragedy can strike with many women and children killed by stray bullets.

Yet, Pastor Engel and his team press on, undeterred by setbacks or the constant threat of violence. "People close to me have died in this gang violence... my own brother-in-law was shot in this gang violence," he shares, but asserts, "I didn't stop doing this work." He acknowledges the "fear" and "anxiety" that cripple society but remains driven by "a cause."

The resounding message from both the community and Pastor Engel is one of self-reliance and unyielding determination.

"Nobody's going to come from anywhere to help to save us, not from overseas, not from our local government; nobody's going to come with a magic wand to cure the Cape Flats. As individuals we need to be so determined to build up resilience, create hope for our people and to grow because politics has clearly failed us," he said.