A Christian civil liberties group has accused South Africa’s Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities (CRL Rights Commission) of misleading the public about its intentions toward churches, warning that a proposed “self-regulatory” framework masks a deeper push toward state regulation of Christian institutions.

At the center of the dispute is the CRL Rights Commission’s Section 22 Draft Self-Regulatory Framework for the Christian Sector, developed through a special ad hoc committee. The Commission has repeatedly insisted that it is not seeking to regulate churches, describing the initiative as voluntary and consultative.

In a statement issued on Jan. 22, the South African Church Defenders (SACD) said it was “deeply concerned” by a recent media briefing held by the CRL Rights Commission. According to SACD, the briefing failed to provide a truthful account of the Commission’s own documents and public record.

“The public was presented with statements that directly contradict the Commission’s official documents,” the group said, describing the briefing as deceptive rather than merely unclear or poorly communicated.

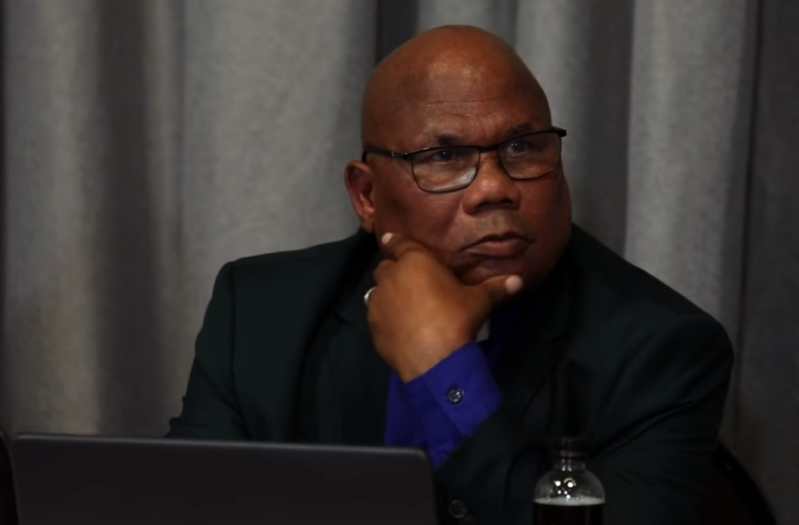

In a press briefing on Jan. 21, the commission responded to a statement made by the former chairperson Professor Musa Xulu, who had alleged that there was a pre-determined agenda to control religious activities through the state.

The SACD group points specifically to clause 2.3 of the draft framework, which calls for nationwide consultations toward the development of a legislative framework for the Christian sector. SACD says this clause directly contradicts public claims that no legislation is being pursued.

“SACD rejects as false and misleading the claim that the CRL Rights Commission is not pursuing legislation or a legal framework for the Christian sector,” the statement reads. “This denial is directly contradicted by the Commission’s own draft framework.”

According to SACD, the framework is designed to establish sector-wide regulatory bodies, enforce registration of Christian institutions and leaders, and impose binding codes of conduct. While the Commission has framed these measures as part of a self-regulatory process, SACD argues that they amount to regulation in substance, if not in name.

The group accused the Commission of presenting “self-regulation” as a public-facing concept while quietly advancing mechanisms that would ultimately place churches under state-linked control. “This is a direct contradiction between what the Commission says and what it is doing,” SACD said.

SACD warned that once a legal framework is drafted, the process would move through consultations and eventually to recommendations to Parliament. At that stage, the group said, lawmakers could be presented with a record suggesting broad participation and consent, making approval more likely.

“This is precisely how legislation is formulated,” the statement said, urging churches to remain vigilant and oppose the process early rather than after it has gained momentum.

The organization also took aim at the tone and purpose of the CRL Rights Commission’s media briefing, suggesting it was an exercise in damage control rather than a genuine attempt to engage critics following the resignation of Xulu.

Without quoting Xulu directly, SACD said efforts to discredit his concerns only deepened public unease about the process. “Institutions of Chapter 9 stature are meant to uphold the highest standards of moral authority and public trust,” the statement said, adding that contradiction and concealment undermine the legitimacy of both the institution and its work.

For these reasons, SACD reiterated its call for the immediate removal of the CRL chairperson and the disbandment of the Section 22 Ad Hoc Committee.

The group said it was “totally opposed” to any legal or legislative framework that seeks to regulate Christian belief, governance, leadership, or practice. Religious freedom, it said, is protected by South Africa’s Constitution and cannot be subordinated to state-controlled structures, even under the banner of consultation or accountability.

SACD also sought to clarify what it sees as a mischaracterization of its position. It rejected claims that its opposition centers on a government White Paper, saying instead that its concerns relate to constitutional limits, lawful process, and the scope of authority granted to the CRL Rights Commission.

“The case is about the constitutionality of the Section 22 Ad Hoc Committee, the failure to follow proper lawful processes, and the protection of freedom of religion,” the statement said.

While the January statement itself does not announce new legal action, SACD’s position must be understood against a broader backdrop of public conflict between church groups and the CRL Rights Commission.

Previous media reports have documented that SACD and allied church leaders have, in recent months, challenged the Commission’s actions through legal channels, arguing that earlier attempts to regulate religious institutions exceeded constitutional boundaries. Those cases and applications have been reported by several South African news outlets and have framed SACD as one of the most vocal opponents of expanded CRL oversight.

In separate reporting, the CRL Rights Commission has defended its approach, saying the framework is intended to protect congregants from abuse and exploitation and to promote ethical leadership within faith communities. The Commission has insisted that participation would be voluntary and that it has no intention of policing doctrine or belief.

Other church bodies have taken more cautious or mixed positions. The South African Council of Churches (SACC), for example, has acknowledged concerns about abuse within religious spaces while urging dialogue rather than confrontation, according to previous public statements reported in the media.

The resignation of Professor Xulu has further intensified scrutiny of the Section 22 process. The former Chair of the commission described internal tensions and confusion over the committee’s mandate, reinforcing claims that the initiative has been poorly defined and contested even among its architects.

For SACD, however, the issue is not one of internal disagreement but of constitutional principle. The organization says the CRL Rights Commission cannot deny legislative intent while advancing documents that explicitly call for it.

“South Africans are entitled to honesty, clarity, and constitutional fidelity,” the statement concluded. “The CRL Rights Commission cannot publicly deny its legislative intentions while advancing a framework that expressly calls for them.”

SACD said it remains committed to defending religious freedom, constitutional supremacy, and the rule of law.

South Africa’s move would mirror steps being taken or considered elsewhere on the continent. Kenya is mulling the introduction of laws that would oversee religious organisations, including stricter registration, financial reporting, and state oversight following cases of abuse and exploitation. Rwanda has already implemented tight regulations that require faith-based groups to meet strict registration, leadership, and safety standards, with authorities closing thousands of churches that fail to comply.